In a new initiative, I am publishing a guest blog for the first time. This one, by tennis enthusiast and freelance writer Jonny Rowntree, explores some aspects of Wimbledon’s historical relationship with advertising. If you would like to consider writing a guest blog on an aspect of sports history for this site, please contact me using the details on the Contact page.

The Wimbledon logo, 2014

Since the first Wimbledon tournament in 1877, tennis’ most prestigious event has become the grand stage of dramatic flourishes, redemption and reclamation. Even for non-tennis enthusiasts, Wimbledon has become a tradition that illuminates television sets in pubs and living rooms across the world, its logo as synonymous with the sport as the legends that have graced its turf. Larger than life personalities, wide media coverage, and a successful branding have forged the venue’s legacy.

In this article, we take a behind the scenes look into the oldest tennis tournament in the world and how it has cultivated and maintains the traditional image established in the early days of the game, and how Wimbledon is evolving and adapting to new technologies and developments in marketing and advertising.

1894 Programme for the Championship

Times have changed considerably from the first black and white print poster in 1894 highlighting the “Lawn Tennis Championships”. This initial break into the event is an excellent lesson in typography and there is a great sense of drama and anticipation, truly announcing itself in turn of the century style. The All-England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club (AELTCC), the organisers of the Wimbledon tennis tournament, would print its first programme in the same year, outlining the court layout and a train schedule, all for threepence.

While these designs would change considerably, the Club wanted to maintain the spirit of its initial presence as a traditional private court, which kept clothing to white and advertising to a minimum.

Perry created posters fr London Transport until 1937

In 1928, London Transport employed artist Frederick Herry Perry to design a series of posters to promote services to Southfields tube station. This saw a considerable move towards livelier colours than in the earlier materials, creating a minimalist narrative with echoes of Art Deco. The 1931 poster was displayed in Underground stations, ticket offices and train carriages. Perry’s innovative design and inclusive graphics helped to open up Wimbledon to the greater public in terms of interest. The masterminds behind the marketing understood this all too well as they continued to target specific stations like Wimbledon itself and Southfields, which is closer to the grounds and was emphasized in the 1931 poster. Perry’s connection with the Underground Group and London Transport enabled him to continue his impressive career with Wimbledon until 1937, the year the event was broadcast for the first time on television.

Wimbledon’s publicity was increased considerably in the 1980s by the work of Tennis Week’s John Davies, illustrator for both posters and magazine covers. These combined a colourful, pastoral style reflecting vintage eras of the traditional English pastime. Davies’ work is a reflection of Wimbledon’s eagerness to present the event as a distinctly English occasion.

Rolex timekeeping at Wimbledon

Ralph Lauren branded uniform for ball girls and boys

As television and radio coverage expanded over the years, the question of further sponsorship opportunities arose. Wimbledon increased in popularity, with 300,000 attending the championship throughout the 1970s, 400,000 towards the late 1980s and the 2010 tournament attracting 500,000 people, according to ESPN. In this context, and with an eye on Wimbledon’s prestigious brand, the organisers resolved to keep sponsorship to a minimum, with only minimal advertising from brands that would appeal to the ABC1 demographic that the event famously attracts. Rather than bring in perimeter advertising or tournament sponsorship, as other sports were doing at this time, Wimbledon restricted advertising to elite makers’ names on essential equipment. Rolex, the official timekeeper from 1978, thus appeared on scoreboards and courtside clocks, IBM’s logo appeared on the service speed board, while other names have been like Slazenger (which has been there since 1902) and Ralph Lauren, which arrived in 2006.

IBM branded service speed board

Eager to keep afloat in modern times, Wimbledon went online in 1995. The official website has grown considerably, from 3.2 million to 19.6 million visitors when comparing 2001 to 2013. Additionally, with the growth of smartphone ownership in the late 2000s, Wimbledon commissioned IBM to create a bespoke app which has been downloaded by over 1.7 million users.

Wimbledon’s commitment to solidifying its brand and not selling out to sponsors has paid off – 2010 alone saw a surplus of £31 million. Wimbledon referee Alan Mills stated that if the AELTCC decked out the tournament in a fashion like the US Open, then ‘It wouldn’t be Wimbledon, would it?’.

Arguably, Mills’ statement could be dismissed as somewhat passé given the number of apparently traditional sporting events that have embraced sponsorship, such as golf’s Open Championship, which began in 1860 and is debatably as steeped in tradition and ritual as Wimbledon, yet sees players sporting outfits emblazoned with their sponsors’ logos and hoardings around the course promoting corporate partnerships.

With this example in mind, however, we could argue that golf has lost some of its tradition and apparently exclusive allure, and the same thing could potentially happen to Wimbledon if it’s brand of tradition was broken. That is to say that key sponsors, partners, and brands that associate themselves with the event will lose interest due to the reduced exclusivity and perceived debasement of the event if less prestigious brands were allowed to advertise there.

In an interview with the UK Tennis Industry Association in 2013, Sir Martin Sorrel, CEO of WPP Group (also known for being group finance director at Saatchi & Saatchi), claimed that ‘outside of the Olympic Games and the World Cup, Wimbledon is the most powerful sports property’, with a worldwide audience of more than one billion. While Wimbledon continues to tread slowly into the domain of sponsorship, its selections are carefully attuned to its brand. Stella Artois joined in 2014 as official supplier in a contract which ends in 2018 as a part of ‘The World’s Greatest Events’ campaign, while Pimm’s continues to be sold as one of the two staple drinks at the Wimbledon tennis tournament.

Sony promoted their range of 4K televisions during Wimbledon using a player’s nails

With these restrictions in place, sponsors have had to find innovative ways of marketing, and social media has proved indispensable as a means of doing this. Andy Murray’s popular Twitter presence was partly helped by a rigorous social media campaign by his sponsor Adidas. Tech companies like Sony have capitalised on the high-definition revolution by using footage of Wimbledon players like Anne Keothavong to showcase tiny logos that can be seen only on their 4k screens.

The use of modern advertising and marketing practices and channels has allowed Wimbledon to continue to thrive whilst not losing its traditional image. Viewers can connect with the tournament through marketing promotions produced not only by its official suppliers, but also by brands using the umbrella of the Wimbledon tennis tournament.

Jonny Rowntree, @shoutjonny, St Ermin’s Hotel

I’ve just visited ‘The Lyons Teashops Lithographs: Art in a Time of Austerity 1946 – 1955’, the wonderful exhibition of late 1940s and early 1950s prints that has been curated by

I’ve just visited ‘The Lyons Teashops Lithographs: Art in a Time of Austerity 1946 – 1955’, the wonderful exhibition of late 1940s and early 1950s prints that has been curated by  Another highlight was my trip to Japan in March, where I gave the keynote paper at the Comparative Sport History Seminar between the UK and Japan, at Ryukoju University (Omiya Campus) in Kyoto. I also gave a talk at Yamaguchi University, where my host, Dr Keiko Ikeda, was teaching. It was an unforgettable experience, full of new sights and new foods, and a range of experiences. As well as meeting some wonderful Japanese colleagues with a passion for sports history, I made my karaoke debut with I Fought the Law, woke up at 2am in my 8th floor hotel room to realise I was in an earthquake, and treated myself to a 7 mile aimless wander around Kyoto. I also visited one of the key sites in twentieth century history when Keiko took me to Hiroshima. I found the overarching narrative of victim-hood without context in the

Another highlight was my trip to Japan in March, where I gave the keynote paper at the Comparative Sport History Seminar between the UK and Japan, at Ryukoju University (Omiya Campus) in Kyoto. I also gave a talk at Yamaguchi University, where my host, Dr Keiko Ikeda, was teaching. It was an unforgettable experience, full of new sights and new foods, and a range of experiences. As well as meeting some wonderful Japanese colleagues with a passion for sports history, I made my karaoke debut with I Fought the Law, woke up at 2am in my 8th floor hotel room to realise I was in an earthquake, and treated myself to a 7 mile aimless wander around Kyoto. I also visited one of the key sites in twentieth century history when Keiko took me to Hiroshima. I found the overarching narrative of victim-hood without context in the

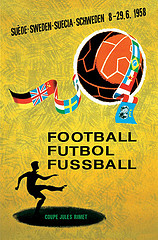

In the week that the England women’s football team made further steps towards qualifying for the 2015 World Cup, the men’s team made their fastest ever departure from the World Cup finals. Following defeats by Italy and Uruguay, England crashed out from Brazil after just two matches. Cue the press clamour for historical comparisons: this was, we were quickly told, the worst England World Cup performance since 1958, which was the last time that England failed to get through the group stage. These kind of comparisons are helpful to a degree, as they give us some kind of perspective and put down some historical markers: but just as when the British Olympic medal haul of 2012 was billed as ‘the best since 1908’, it is easy to overlook the contexts of those earlier events. So, what was England’s 1958 World Cup campaign in Sweden all about? Was it as bad as 2014?

In the week that the England women’s football team made further steps towards qualifying for the 2015 World Cup, the men’s team made their fastest ever departure from the World Cup finals. Following defeats by Italy and Uruguay, England crashed out from Brazil after just two matches. Cue the press clamour for historical comparisons: this was, we were quickly told, the worst England World Cup performance since 1958, which was the last time that England failed to get through the group stage. These kind of comparisons are helpful to a degree, as they give us some kind of perspective and put down some historical markers: but just as when the British Olympic medal haul of 2012 was billed as ‘the best since 1908’, it is easy to overlook the contexts of those earlier events. So, what was England’s 1958 World Cup campaign in Sweden all about? Was it as bad as 2014?