This weekend, winter sports fans will have their eyes glued on Sochi in Russia, where the 22nd Winter Olympics are due to begin. The Winter version of the Olympic franchise do not have the same global appeal as their Summer counterparts, as the twin constraints of geography and costs keep many nations out: compared to the 204 teams that competed at London 2012, the most recent Summer Olympics, the last Winter Olympics in Vancouver attracted 82 nations. Still, the Winter Olympics have grown in appeal and scope over the eighty years of their official history, and they provide spectacle and drama in equal measure on the ice and on the slopes. The fact that this year’s Olympics have already attracted so much controversy, due to Russia’s human rights record, the Games’ environmental impact, and the country’s draconian treatment of homosexuals, is a sign of how big the Winter Games getting – they are now (rightly) as political contested as the Summer Olympics.

I’ve written about the Sochi LGBT debate for the Free Word Centre, although I am fascinated to see how it pans out now that the Games are on us and many people have made their sentiments clear: Barrack Obama’s decision to send Billie Jean King as one of his representatives is my favourite piece of provocation so far. What I want to do here is to think more historically about the prehistory of the Winter Olympics, particularly the series of sports that were held as part of the 1908 London Olympics under the name of the Olympic Winter Games of the Olympic Winter Programme.

Poster for the 1924 Winter Sports at Chamonix

The official version has Chamonix 1924 as the first Winter Olympics, although it is well to remember, as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) themselves point out, that this appellation was granted only retrospectively: at the time, these sports that attracted competitors from 16 nations to the French Alps were simply held in conjunction with that year’s Paris Olympics. The 1928 Games at St Moritz were really the first to be organised under IOC auspices – and, of course, it is only from this period that we should refer to the other Olympics as the Summer Olympics: it’s anachronistic to apply this term to any Olympics before 1924. But Chamonix was not the first time that Olympic organisers had experimented with winter sports. Ice hockey featured in the 1920 Olympics at Antwerp (Canada won, of course), as did figure skating, in which five nations competed across singles events for men and women and a mixed pairs event. But it is to London in 1908 that we really need to look for the start of this prehistory.

The 1908 Olympics started on 27 April, with the opening matches in the racquets tournament at Queen’s Club. Events were then spread across May and June, with the main two weeks of stadium-based events running at the Great Stadium in the Franco-British Exhibition grounds from 13-25 July. Sailing and motorboating took place in July and August, and then there was a break until 19 October. It was on this day that the Winter programme was launched. The idea had developed during the British Olympic Council’s planning for the Games. Their minutes of 20 December 1906, for example, record the discussion of ‘the possibility of holding Olympic Skating Competitions in the winter of 1907-08’, and the planning for what they soon referred to as the ‘Winter Sports’ and the ‘Winter Games’ carried on as the Games approached, with the dates being set at the Council’s meeting on 15 November 1907: ‘The Winter Games were definitely appointed to commence on Monday, October 19, 1908’, and a Winter Games Committee was subsequently set up to plan the events. Figure and sped skating were both discussed, with the former kept and the latter dropped, and the Committee decided to hold the team sports played in Britain in winter as part of this experimental programme. Football, hockey, lacrosse, and rugby thus found themselves as part of the first Winter Games.

Great Britain’s football team at the 1908 Olympic Games

The Winter Programme started at the Stadium on 19 October, as planned, with Denmark beating France B 9-0 in the football. Over the next two weeks, the team sports all took place. Great Britain won the football, beating Denmark 2-0 in the final watched by just 8,000 people. The hockey was also won by Great Britain, though this was a tournament in which England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales entered separate teams, all under the name of Great Britain, with France and Germany making up the numbers. The final saw England beat Ireland 8-1 in front of 5,000 people. The lacrosse tournament had an even lower profile: with only two teams involved, Canada and Great Britain, there was only one match, with Canada taking gold medal after a 14-10 victory. The rugby was similarly low-key, a two-team tournament between the touring Australian side and the British county champions, Cornwall, although the record books have to show this as Great Britain. Australia won 32-3. As well as these team sports, the Winter Programme involved boxing, a one-day tournament for five weight classes at the Northampton Institute in Clerkenwell.

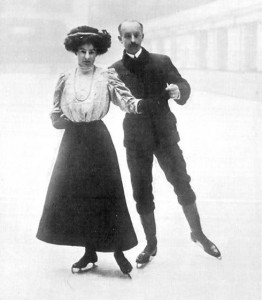

Madge and Edgar Syers

It is what happened at Prince’s Skating Club, Knightsbridge, however, that makes this Winter Programme of the 1908 Olympics so significant. For here, on 28 and 29 October, the figure skating took place, the first time in Olympic history that an ice-based sport had featured. Prince’s Club was a private members establishment which had been running since 1896. For the Olympics, it hosted four competitions: Individual events for Gentlemen and Ladies; a Special Figures event for Gentlemen; and Pairs Skating. The last of these was pioneering, not just for it being an ice-based sport, but as the first time that the Olympics had included a mixed-sex aesthetic sport. Inevitably, the competition was rather small: this was an expensive niche sport at the time, and only 21 competitors from 6 nations took part. However, this included leading figures in the sport, such as the Swede Ulrich Salchow (whose name we will hear a lot from Sochi as skaters attempt their double and triple Salchows), world champion every year bar one between 1901 and 1911, and Madge Syers of Britain, whose entry in the 1902 men’s world championships had forced the International Skating Union to create a separate event for women. Over the two days of competition, the four gold medals went to Sweden, Russia, Germany, and Great Britain, Syers winning the Ladies’ event and also winning bronze with her husband Edgar in the Pairs. The skating events attracted a great deal of press attention, with pictorial features in many of the dailies and large technical coverage in The Field, and the Olympics certainly helped to popularise skating in Britain.

Ulrich Salchow

It is impossible to claim that what happened in London in October 1908 was the first Winter Olympics. That phrase has no currency until the 1920s, when separate events, under the IOC’s auspices and featuring only alpine and ice-based sports, were first held. However, this Winter Programme was a crucial moment in Olympic history, not least for bringing ice into the equation. As historians, we should look back at this moment in the prehistory of Sochi 2014 for a reminder that the Olympics have always been experimental, and that the programme has never fossilised.