Before my swim at the Aquatics Centre

During the recent school holiday, I went swimming with my 13 year old son. Not such a big deal – except this time we went to the Olympic pool at the London Aquatics Centre. It was only my second time in a 50 metre pool – and as the first one was a splash around in the 1970 Commonwealth Games pool in Edinburgh when I was in the city on a family holiday in the early 1970s, before I has learnt to swim, it doesn’t really count. For my son, it was a first. We were both impressed by the whole experience – the size, the scale, the way the light fills the space now that the temporary seats have gone, the stunning curves of the Zaha Hadid‘s design, as well as the sense of distance that comes with a 50 metre pool for people like us who are used to only 25 metres. As well as the swim, I was most impressed with the way in which the Centre is being managed for its community. With prices that match those at other pools in the area, and with public access to the competition pool and the training pool, this is a great example of Olympic legacy at work. I remain to be convinced about the plan to turn the Olympic Stadium into a football ground, but my feeling is that they have got it spot on with the pool. They even serve hot Bovril in the cafe.

Swimming at the London 2012 site has led me to reflect on the aquatics sites for London’s previous Olympic and Olympian Games, and how far these sites added to the capital’s swimscape.

The River Thames at Teddington Lock

If we go back to the pre-Coubertin period, the planners of the National Olympian Festival of 1866 held their swimming events in the River Thames. They chose Teddington, where the lock, built in 1811, marks the end of the river’s tidal reach. Here, on a rainy and windy July evening, swimmers competed for the first medals of these first games to be staged by the National Olympian Association. With a moored barge marking the start, swimmers from London and beyond took part in three races – the quarter mile, the half mile, and the mile. Nothing was purpose built for this Olympian festival – the athletics took place the next day in the park at Crystal Palace, and the gymnastics and ‘antagonistic sports’ were at the German Gymnasium in Kings Cross. London’s first Olympian swimming event was thus a fairly modest affair, making use of a natural space where plenty of people regularly swam, and it is impossible to see any kind of impact on London’s swimming spaces.

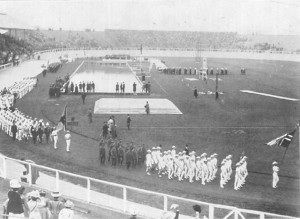

The opening ceremony of the 1908 Olympic Games, with the swimming pool in the background

In 1908, when London first hosted the International Olympic Committee’s Olympic Games, the British Olympic Association commissioned the world’s first purpose-built Olympic Stadium in the west London suburb of Shepherd’s Bush as part of the Franco-British Exhibition. The planners wanted to fit as many sports into the Stadium as possible, and the aquatic sports of swimming, diving, and water polo were part of this vision. Accordingly, engineer Paul Webster built an open air pool into the infield of the Great Stadium. Despite the running tracks and the cycling track being built to imperial distances, the pool was metric, a whopping 100 metres long, and a 10 metre diving tower that could be lowered under the water when the pool was being used for swimming and water polo. The pool – sometimes referred to as the swimming tank – was well placed for the crowds, but was clearly far from ideal for the swimmers. There was no heating and no filtration system, and the water was made filthy by some athletes jumping in to cool off, muddy legs and all, after their races. After the Olympics, the pool was used for various things, including an angling competition, and it served as an unintentional water obstacle for the Olympic rugby union, hockey, football, and lacrosse competitions that took place on the in-field in October. However, with public baths al over London by this time, many with the all-weather advantage of being indoors and the water quality advantage of filtering, there was no significant demand for the pool. It was soon drained and filled in: and while the re-named White City Stadium had a long sporting afterlife when the Olympics had finished, featuring athletics, speedway, greyhound racing, football, and more, there was no to be no aquatic legacy of the 1908 Olympics.

Empire Pool, Wembley

When the Olympics returned to London in 1948, there was no budget for significant new building, and the Games had to fit into the capital’s existing venues. With Wembley chosen as the hub of the Games, the planners were working around the presence of an excellent aquatics site. The Empire Pool had been built by Owen Williams for the 1934 British Empire Games, the second iteration of the series that has since evolved into the Commonwealth Games. It was already set up for up to 7,000 spectators, and positioned just yards from the Empire Stadium, it was the perfect fit. At the 1948 Olympics, not only did it host the swimming and diving, and the final stages of the water polo, it also did service as a boxing venue, with a ring erected on scaffold over the water – the perfect example of make do and mend that characterised these Olympics. However, just as the 1908 pool so very little post-Olympic swimming action. As Ian Gordon and Simon Inglis show in their Great Lengths, the pool had been a massive hit after the 1934 Empire Games, attracting huge crowds. It had also doubled up as a venue for ice skating and ice hockey in winter, with a rink being created on boarding placed over the pool. But it had closed during the War and it was only re-opened for the Olympics. The building, re-branded Wembley Arena, is still going strong, but its days as a swimming pool are long gone.

And so to 2012. These earlier Olympics took place in the years PL (pre-Legacy), when Olympics did not have to have plans for the city’s future built into them. They made no long-term impact on where Londoners swam. Now that we are in the legacy phase of 2012, it is useful to compare the Aquatics Centre with the earlier sites of Teddington Lock, White City, and the Empire Pool, and to see how making a community pool with the capacity for international competition was a great part of the project.

See you in the medium-paced lane sometime soon.

On Friday 4 November 2011, I’m giving a talk at the

On Friday 4 November 2011, I’m giving a talk at the