“So he sent his doting mother / Up the stairs with the stepladder, / To get the Subbuteo out of the loft”

It's Saturday tea time in a London suburb in the mid-1970s. I am 10 years old. I have spent the afternoon watching World of Sport on ITV, presented by Dickie Davies. The highlight of the show was the wrestling, with Big Daddy and Giant Haystacks putting on a choreographed display of Nelsons and Boston Crabs for the old ladies in the audience and the rest of us at home. The football scores have come in – Tranmere Rovers have lost. My mum has just made tea, crispy pancakes followed by and arctic roll. After tea, we watch Bruce Forsyth on The Generation Game urging other families through the humiliations of turning the potters' wheel. My brother, bored, doodles on the sole of his Woolworths slippers with a biro.

It could never have crossed my mind that, ten years later, I would be listening to a post- punk band from Merseyside eulogizing this kind of scene, celebrating it with a 'contemptuous nostalgia. It turned out that Half Man Half Biscuit had sucked up what Taylor Parkes called the 'cultural detritus'[1] of the late 1960s and 1970s, and turned it into surreal and satirical songs. Categorised as 'comedy punk' by the Rough Guide to Punk,[2] and hailed by BBC DJ Andy Kershaw as 'the most complete and authentic British band since The Clash',[3] Half Man Half Biscuit created an original body of work out of the least promising ingredients.

Like most people who heard Half Man Half Biscuit at the time, I first came across them on John Peel's late night show on BBC Radio 1. Peel's show was where so many of us first heard music that would not figure elsewhere, and would never make it to Top of the Pops. He played the edgy, the risky, the original, and the downright strange. Half Man Half Biscuit fitted all of these bills, and in Peel they had a champion. Indeed, as one Peelite later put it when the DJ came 43rd in a poll of the most important people in British history, 'Can't believe they gave that Greatest Briton shit to Churchill when there's a man among us who still plays Half Man Half Biscuit records on the taxpayer's buck'.[4]

That was later. At the time, the band's daft name grabbed my attention. Then the songs took over, particularly 'The Trumpton Riots', a tale of the idyllic world of a 1970s children's TV show being torn apart by a revolutionary militia who assassinate the mayor . Other songs on the Peel sessions took an equally bizarre glance at popular culture, with advertisements, comedy stars, football teams, ordinary places, and processed food brands all finding themselves name checked in odd and sometimes disturbing combinations. There was 'Arthur's Farm', a nightmare vision of famous amputees Arthur Askey and Douglas Bader taking over Orwell's Animal Farm with the new motto 'Four Legs Good but No Legs Best'.[5] And, of course, there was a track that appealed to the football fan in me, their ode to Subbuteo, 'All I Want for Christmas is the Dukla Prague Away Kit'. When their first album came out, I made the long trip from my university at Lampeter to Swansea to buy it. Back at my student digs, a two-floor flat above a dentists' surgery that always smelled of mouthwash, I played it to friends. I didn't exactly acquire cult status by association, but I know that the other Peelites loved it, while most friends smiled in pity and went back to Madonna and A-Ha.

What was it about Back in the DHSS that so appealed to me then, and that has made it an album I frequently return to even when I should, at 48, be old enough to know better? In what ways is it as representative of its time as other indie albums from 1985, like The Smiths' Meat Is Murder, Psychocandy by The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Pogues' Rum, Sodomy and The Lash, or This Nation's Saving Grace by The Fall?

Half Man Half Biscuit have carried on since 1985, and have to date released 13 albums, their titles showing that the vision of surrealism, satire and trash that drove Back in the DHSS has not diminished. Some Call It Godcore (1995), Voyage to the Bottom of the Road (1997), Achtung Bono (2005) and CSI Ambleside (2008) suggest a weird view of the world and a willingness to act both a celebrants of the mundane and as iconoclasts to the famous. Some of these albums are better than Back in the DHSS: they have, unsurprisingly, higher production values, greater instrumental skills, and wider musical palettes than the drum/bass/guitar and wailing synth of their first outing. Taylor Parkes has gone so far as to call Back in the DHSS 'something of a millstone',[6] as it has left the band remembered as a comedy punk band when their later output has so much more to it. But the fact that Back in the DHSS came first gives it the edge as a historical document that needs celebration.

A persistent target in Half Man Half Biscuit's songs has been the 'bands who got a bit pompous'.[7] They warn us the groups who 'type out their set lists',[8] and they mock the people who, through collaborations with Brian Eno, 'put the con in concept'.[9] All of these barbs are accurate. However, Back in the DHSS has a feel of a manifesto about it. It was aggressively uncommercial, with a production style and level of musicianship that turned the clock back from post-punk to punk. The front cover was filled with an out of focus photograph of bass player Neil Crossley rendered in lurid pinks and blues. The album was deeply personal, with lyrics that embodied writer Nigel Blackwell's vision, and it was full of references and in-jokes that nobody was going to explain. If you didn't know who Fred Titmuss, Tony Bastable, or Nerys Hughes were, or what was funny about someone trying to kill himself with a Haliborange overdose, then the album wasn't really for you. The manifesto was that all of these bits of pop culture were worth laughing at and singing about, and that satire and surrealism could co-habit in a landscape that combined TV puppet shows, suburban kitchens, hospital waiting rooms, and football terraces, and where Lev Yashin and Marilyn Monroe could pop up with Jim Reeves, Jesus Christ, and Lech Walesa.

Of course, Half Man Half Biscuit drew from a number of traditions. Punk was the most obvious and

immediate, and was evident in their instrumental skills, their unpolished vocals, and the simplicity of most of their arrangements, right down to the singer standing too close to the studio microphone so that all of his Ps popped. Punk was also there in their attitude: not necessarily hostile, but certainly uncompromising and uninterested in some of the trappings of the pop scene.

Tranmere Rovers, 1919

Then there was the Merseyside tradition, later name checked in an album title that poked fun at the more famous band from the other side of the river, Four Lads Who Shook The Wirral, and evident in this album's dole age play on The Beatles' 'Back in the USSR'. After the Mersey boom of the 1960s, the city had produced a number of punk bands but was, in the early 1980s, most famous for a diverse range of post-punk bands, including the art school spiky guitars of Echo and the Bunnymen, the cool synth pop of Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, the organ-driven psychedelia of The Teardrop Explodes, and the hi-energy gloss of Frankie Goes To Hollywood. To an outsider, Half Man Half Biscuit didn't seem to part of a scene in the way that Echo and Teardrop did, but they name checked local and regional places, they sang in Liverpool accents, and they put Tranmere Rovers ahead of The Tube.

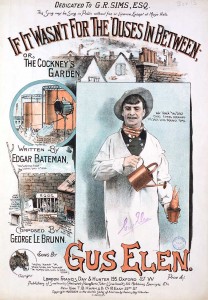

“The dustcart though it seldom comes, is just like 'arvest 'ome / And we mean to rig a dairy up some'ow”

Finally, Half Man Half Biscuit were tapping into a comedy tradition that went back to music hall, and had other proponents in the punk and post-punk scene. Like music hall singers, Half Man Half Biscuits were able to make comedy out of everyday and mundane places and situations. The queue of pensioners at the post office 'Sealclubbing', or the dismal relationship charted in 'Reflections in A Flat', create a mood close to the working class lives captured in classic music hall. Surely, if there hadn't already been songs from the halls called 'Our Lodger's Such a Nice Young Man', or 'The Spaniard that Blighted My Life', then Half Man Half Biscuit would have written them. Since music hall, plenty of major bands and singers had written intentionally funny songs or filled some songs with jokes. Think of Bob Dylan pulling down his pants when the bank manager asked him for some collateral in 'Bob Dylan's 115th Dream', or of the Wild West femme fatalle in The Beatles' 'Rocky Racoon' whose 'name was McGill, but she called herself Lill, and everyone knew her as Nancy'. Some bands made a career of comic songs, like Dave Dee Dozy Beaky Mick and Tich and, at the more art school end of the spectrum, The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. By the 1970s, comedy hits tended to be either excruciating pastiches, like the Barron Knights' take on the Brotherhood of Man (a marriage made in pop music purgatory if ever there was one), or songs sung in local dialects, from the West Country yokelese of The Wurzels to the cockney knees-up of Chas and Dave.

Despite punk's reputation for street politics and earnestness, this movement brought with it many acts and songs that were essentially comedy. Jilted John's eponymous hit of 1978 had unrequited lovers everywhere chanting 'Gordon is a moron', Spizzenergi paid tribute to Star Trek in their 1979 single 'Where's Captain Kirk?', Splodgenessabounds summed up the frustration of trying to get served in a busy pub in 'Two Pints of Lager and a Packet of Crisps Please' in 1980, and Tenpole Tudor went mock medieval on us with 'Swords of a Thousand Men' in 1981. To listeners, Half Man Half Biscuit were certainly part of this tradition. They added to it, though, both through the surrealism of the juxtapositions, the ordinariness of the things they sung about, their highly literate writing style, and the frequently depressed and angry mood that underpinned the humour. And, where other bands name-checked to show off their credentials, like Duran Duran dropping Voltaire into 'Last Chance on a Stairway' and Lloyd Cole populating his first album Rattlesnakes with Eva Marie Saint and Norman Mailer, Half Man Half Biscuit went distinctly low culture on us with television magician Ali Bongo and snooker referee Len Ganley.

It was this combination that won me over as a fan in 1985. I lapped it all up, from the rough production to the smooth puns, and I celebrated in a band that could make punk poetry out of everyday life, and could make it both funny and moving.

Half Man Half Biscuit belong to many traditions in popular music. Perhaps the overarching one is of English eccentricity, a catch-all label that covers acts, both cult and mainstream, who have tapped into particular memories and tropes, and have created a music that is funny, provocative, nostaligic, ironic, and true. They belong here with Robyn Hitchcock, The Kinks, Ian Dury, and Madness. Back in the DHSS, the opening blast of their career, deserves to be explored and celebrated.

[2] Al Spicer, The Rough Guide to Punk, London: Rough Guides 2006, pp.155-6,

[3] Quoted in Rob Hughes, ‘The Stars That Fame Forgot: Half Man Half Biscuit’, Uncut, June 2008, p.22.

[4] Quoted in John Peel, Margrave of the Marshes: his autobiography, London: Bantam Press, 2005, p.442.

zp8497586rq

Another highlight was my trip to Japan in March, where I gave the keynote paper at the Comparative Sport History Seminar between the UK and Japan, at Ryukoju University (Omiya Campus) in Kyoto. I also gave a talk at Yamaguchi University, where my host, Dr Keiko Ikeda, was teaching. It was an unforgettable experience, full of new sights and new foods, and a range of experiences. As well as meeting some wonderful Japanese colleagues with a passion for sports history, I made my karaoke debut with I Fought the Law, woke up at 2am in my 8th floor hotel room to realise I was in an earthquake, and treated myself to a 7 mile aimless wander around Kyoto. I also visited one of the key sites in twentieth century history when Keiko took me to Hiroshima. I found the overarching narrative of victim-hood without context in the Peace Memorial Museum to be problematic, but some of the artefacts, the memorials, and the overall atmosphere were beyond moving.

Another highlight was my trip to Japan in March, where I gave the keynote paper at the Comparative Sport History Seminar between the UK and Japan, at Ryukoju University (Omiya Campus) in Kyoto. I also gave a talk at Yamaguchi University, where my host, Dr Keiko Ikeda, was teaching. It was an unforgettable experience, full of new sights and new foods, and a range of experiences. As well as meeting some wonderful Japanese colleagues with a passion for sports history, I made my karaoke debut with I Fought the Law, woke up at 2am in my 8th floor hotel room to realise I was in an earthquake, and treated myself to a 7 mile aimless wander around Kyoto. I also visited one of the key sites in twentieth century history when Keiko took me to Hiroshima. I found the overarching narrative of victim-hood without context in the Peace Memorial Museum to be problematic, but some of the artefacts, the memorials, and the overall atmosphere were beyond moving.

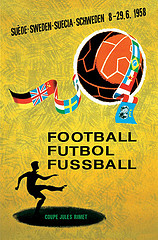

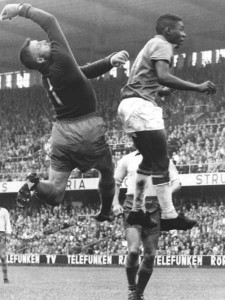

In the week that the England women’s football team made further steps towards qualifying for the 2015 World Cup, the men’s team made their fastest ever departure from the World Cup finals. Following defeats by Italy and Uruguay, England crashed out from Brazil after just two matches. Cue the press clamour for historical comparisons: this was, we were quickly told, the worst England World Cup performance since 1958, which was the last time that England failed to get through the group stage. These kind of comparisons are helpful to a degree, as they give us some kind of perspective and put down some historical markers: but just as when the British Olympic medal haul of 2012 was billed as ‘the best since 1908’, it is easy to overlook the contexts of those earlier events. So, what was England’s 1958 World Cup campaign in Sweden all about? Was it as bad as 2014?

In the week that the England women’s football team made further steps towards qualifying for the 2015 World Cup, the men’s team made their fastest ever departure from the World Cup finals. Following defeats by Italy and Uruguay, England crashed out from Brazil after just two matches. Cue the press clamour for historical comparisons: this was, we were quickly told, the worst England World Cup performance since 1958, which was the last time that England failed to get through the group stage. These kind of comparisons are helpful to a degree, as they give us some kind of perspective and put down some historical markers: but just as when the British Olympic medal haul of 2012 was billed as ‘the best since 1908’, it is easy to overlook the contexts of those earlier events. So, what was England’s 1958 World Cup campaign in Sweden all about? Was it as bad as 2014?

Every year, my brother takes my children, my wife, and me to the theatre as a Christmas treat. It’s a lovely tradition that gives us all an annual highlight, as we experience the best of the West End as a family. This year, we all chose The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Simon Stephens’ adaptation of Mark Haddon’s famous novel about a boy with learning difficulties making sense of his world. We had all read the book, and were keen to see the acclaimed stage version. After meeting for dinner, we made our way through China Town in heavy rain, and got to the Apollo Theatre shortly before the curtain. Our seats in the dress circle gave us a good view of the stage, and gave us a great sense of the ornate Edwardian styling that still defines

Every year, my brother takes my children, my wife, and me to the theatre as a Christmas treat. It’s a lovely tradition that gives us all an annual highlight, as we experience the best of the West End as a family. This year, we all chose The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Simon Stephens’ adaptation of Mark Haddon’s famous novel about a boy with learning difficulties making sense of his world. We had all read the book, and were keen to see the acclaimed stage version. After meeting for dinner, we made our way through China Town in heavy rain, and got to the Apollo Theatre shortly before the curtain. Our seats in the dress circle gave us a good view of the stage, and gave us a great sense of the ornate Edwardian styling that still defines

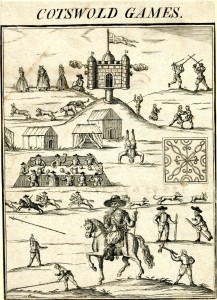

Last weekend, I made what has now become an annual trip to Chipping Campden to watch and take part in Robert Dover’s

Last weekend, I made what has now become an annual trip to Chipping Campden to watch and take part in Robert Dover’s